Bionic eye helps the blind enter new dimensions of sight

The American-made Argus implant ('bionic eye') restores partial vision

to those blinded by retinitis pigmentosa. The second generation of the

implant will hit the European market this summer.

Germany's national health care system has agreed to cover the

Argus, and the United Kingdom and France are likely to follow. With a

100,000 US dollar (70,000 euro) price tag, whether or not the implant

will be able to restore sight to tens of thousands of Europeans won't be

determined by the success of the product, but by the ability of the

manufacturer and medical community to convince other healthcare systems

to pay for it.

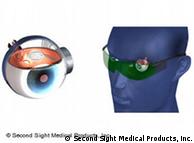

Argus II: Special glasses, a computer, and a chip implanted into the eye Argus II: Special glasses, a computer, and a chip implanted into the eye

Officials are likely to have a hard time denying a blind person the

chance of partially restoring their sight. Terry Byland from Los Angeles

went blind in his forties. Standing outside the Riverside Braille Club,

east of Los Angeles, he says: "The first time I touched that door with

this cane I hit it right in the middle of the door each time. There was

no guess work about where I was going."

Terry Byland is a member of the lively Riverside Braille Club. Most

club members are well adjusted to life without sight. They gather on

Tuesdays for exercise, bingo and choir practice. Before losing his

sight, Terry sold machinery. Shortly after he was diagnosed with

retinitis pigmentosa, his eyesight disappeared, leaving him scared and

frustrated.

Eye works like a camera

In many ways, the eye operates like a camera. For those suffering

from retinitis pigmentosa, like Terry, seeing becomes impossible because

of deteriorating photoreceptors in the retina - the equivalent of

having a layer of camera film missing. The light enters through the lens

and illuminates the film or the retina and transmits the picture of the

outside world to the brain.

The Argus, the artificial retina, communicates with the brain through

electric impulses, just like a full functioning retina would. A small

video camera attached to a pair of glasses sends its picture to a

computer the size of a deck of cards in the user's pocket. The computer

translates the image into electric impulses and wirelessly communicates

the information to electrodes implanted on the back of the eye.

The result is a highly-pixelated black and white picture. "Describing

what they see is very challenging. But what we can do is measure their

performance on tasks," explains Brian Mech of Second Sight Medical

Products in Los Angeles. He has been a leader on the Argus development

team for over a decade. "They can tell if people are approaching or

leaving, into what direction they are moving."

Enhanced features

Terry Byland was one of two patients to receive the first generation

of the implant during the earliest of the clinical trails. His feedback

allowed for the following version to be enhanced, and new features were

added. "I'd give anything to have the new version, but the FDA won't

allow that," says Byland.

Our eye works like a camera. People blinded by retinitis pigmentosa lack a layer of film, so to speak Our eye works like a camera. People blinded by retinitis pigmentosa lack a layer of film, so to speak

The American FDA, or Food and Drug Administration, has yet to give

the green light to the Argus, even though European health officials have

already granted approval. The FDA is notoriously tough, but all in the

name of safety. Others, particularly those holding the purse strings,

have a different set of questions. For example, how much will the

implant affect the lifestyles of those who receive it?

Terry Byland does not wear his glasses everywhere. For instance he

points out, they don't work properly inside the Riverside Braille Club.

"I've had them here before," he says, "and the contrast value here is

lousy. What I mean by that is you walk in there and it is mostly all

vanilla. There's not that much dark and light to work with. And without

that the camera doesn't work that well."

People like Terry Byland who have been blind for a long time already

have ways to compensate, like listening for the traffic of cars to stay

in the lines of a pedestrian crossing. On the other hand, those who have

recently lost their sight might not be so good at these new skills and

may find the implant very useful.

Mind meets machine

The next generations of bionic eye might be different. The Argus II

currently has 60 electrodes, but the team is hoping to develop that

further eventually produce an implant with around two thousand

electrodes. Adding electrodes is similar to adding pixels to a digital

camera - more pixels means a better image.

The Argus II computer is not bigger than a deck of cards The Argus II computer is not bigger than a deck of cards

But there's a limit: "It turns out that God or nature is a much

better engineer than man," warns Mech of Second Sight Medical Products,

referring to the human eye. "At least when it comes to this part,

because we could never build electrodes that are as efficient as our

photodetectors."

While the Argus is an improvement, it has its technological

limitations and is only applicable to a certain group of visually

impaired. Since it's people with retinitis pigmentosa who are only

approved to receive the device, Argus candidates make up a small

fraction of those with advanced vision loss.

The real technological feat of this device is often overlooked,

however. It's the first machine that interfaces directly with the brain

to be made available to the public. So while possibilities of restoring

sight may be limited, the possibilities of mind meets machine are

something to look forward to.

Author: Annie Gilbertson

Editor: Guy Degen

http://www.dw-world.de/dw/article/0,,14989409,00.html

|