Quasiparticle discovery could pave the way for better digital storage

Skyrmions were found on an atomic layer of iron on iridium

German scientists from Jülich, Kiel and Hamburg have found a new

magnetic order that could potentially lead to a new generation of

smaller data storage units in the future.

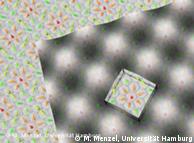

Physicists from the Jülich research center and the universities

of Kiel and Hamburg have found a regular lattice of stable magnetic

skyrmions – radial spiral structures, which are made up of atomic-scale

spins.

These magnetic patterns have been found in large bulk materials

before, but never on a nano-sized surface. The team of scientists,

which published their findings Sunday in the journal Nature Physics,

have theorized that these magnetic structures could lead to smaller and

more efficient data storage units.

"If you had asked me five years ago if such a structure can form, I

would have said no. But nature has its surprises," said Stefan Blügel,

director of the Institute of Quantum Theory of Materials at the Peter

Grünberg Institute at the Jülich national laboratory, and one of the

paper's co-authors.

"We've discovered a new magnetic structure that is an extremely

stable one," he told Deutsche Welle. "This structure is

topologically-protected, and can't be destroyed very easily."

The future of spintronics

Skyrmions were first postulated by a British physicist in the 1950s,

but were not found in nature until decades later. Physicists have

speculated that these quasiparticles might assist the burgeoning

research area of spintronics, which may power the next generation of

consumer gadgets.

This new area physics research is being hailed as the successor of

conventional electronics, based on transistor and semiconductor

technology. In general, for over the last 50 years, the number of

transistors that can be put on an integrated circuit doubles

approximately every 18 to 24 months.

However, the number of transistors is now getting so large, on such a

small space, that it's beginning to hit its physical limits, and will

soon reach the size of individual atoms.

The new findings might lead to smaller and more efficient storage unitsConventional

electronics have been based on harnessing the charge of electrons. When

they move, they generate electric current, which can be used to

transfer information. But electrons can do more than just travel in a

linear direction - one quantum-mechanical characteristic is their

intrinsic spin. Just as an ice skater twirls, so too do electrons. The new findings might lead to smaller and more efficient storage unitsConventional

electronics have been based on harnessing the charge of electrons. When

they move, they generate electric current, which can be used to

transfer information. But electrons can do more than just travel in a

linear direction - one quantum-mechanical characteristic is their

intrinsic spin. Just as an ice skater twirls, so too do electrons.

Spintronics makes use of both the intrinsic spin of the electron and

its fundamental electronic charge. In theory, scientists say that by

harnessing this electronic spin as a way to store data at high-speed and

low-power. Conceivably, that could make internal batteries, or even

booting up a device, completely unecessary.

Earlier research in spintronics paved the way for solid-state flash

memory commonly found nowadays in smartphones and digital cameras.

In the new study, the German scientists found the skyrmions in a thin

layer of iron on iridium, where each spiral was made up of just 15

atoms.

Skyrmions on the surface

"It's extraordinary, because we found it on a surface instead of in bulk materials," Blügel said.

In 2009, scientists from Munich had found a similar structure in bulk

materials, but this new one is 10 times smaller than that previous

discovery.

"But it's a lot easier to observe and manipulate a magnetic structure

on a surface, to write the codes 0 and 1 on the layer," Blügel adds.

Newer laptops have flash memory instead of traditional hard drives"For us, it was surprising that this kind of structure formed after all, and that it was so very small," Blügel said. Newer laptops have flash memory instead of traditional hard drives"For us, it was surprising that this kind of structure formed after all, and that it was so very small," Blügel said.

Other phycisists have been impressed by the new finding.

"It's definitely meaningful for the field of magnetism," said Markus

Garst who participated in the 2009 study, but didn't contribute to the

recent study. "It's important that skyrmions were found in a different

material as well. It's important for fundamental research and proves

that these findings were not just an exotic exception."

Computer users will have to wait a bit longer

According to Ulrich Rössler from the Leibniz Institute for Solid

State and Materials Research in Dresden, who has been researching these

magnetic spirals for some time, these recent findings will mean that a

new field of research may emerge, he wrote in an e-mail sent to Deutsche

Welle.

"Such conditions consisting of countable units are quite rare in physics," he wrote.

But Rössler also added that it's too early to say how soon these findings can be put to use.

Blügel, one of the paper's authors, agreed, saying that it may be at

least a decade before this research bears out into actual

consumer products.

"This is important for storage as resistance comes into play when

reading data," he said. "Maybe in about 10 to 15 years, this can be put

to use in smaller storage units that can hold more data."

Author: Sarah Steffen

Editor: Cyrus Farivar

ttp://www.dw-world.de/dw/article/0,,15285806,00.html

|